This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on environmental justice in the favelas through RioOnWatch.

This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on environmental justice in the favelas through RioOnWatch.

Those who look at Complexo da Maré, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, made up of 16 densely populated favelas, might not immediately associate the area with its natural ecosystem. However, Maré is crisscrossed by an extensive network of waterways that continue to exist beneath pollution, degradation, and aggressive interventions. There, fragments of mangrove vegetation and important watercourses struggle, persisting in the Maré landscape.

A Vast Archipelago Called Maré

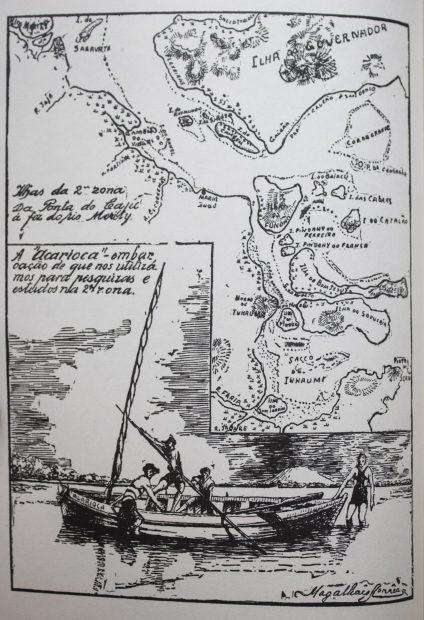

The Maré of yore had lush landscapes and, less than 100 years ago, was made up of beaches, islands, and mangroves. The book Carioca Waters describes the region’s nature in the 1930s based on accounts from writer Armando Magalhães Corrêa (1889–1944).

“Flocks of herons took flight; now standing out are Inhaúma Hill [currently the Morro do Timbau favela], Tibau Point, and Fundão Island. We headed south, passing through the Inhaúma Canal [today, the area crossed by the Linha Amarela expressway]… The upper part of the hill is covered with mango, abiu, tamarind, cashew, and sapodilla [fruit] trees… On the rocks, cacti, and on the trees, bromeliads.” — excerpt from Carioca Waters, by Antonio Carlos Pinto Vieira (2016, p. 145)

The area surrounding today’s Complexo da Maré was once a vast archipelago. Its islands formed channels that helped keep alive the sea that flowed through the area inhabited by the community. The waters of Guanabara Bay stretched far inland, reaching what is now the Brazilian national health foundation (Fiocruz). Within what is now Maré, there was Pinheiro Island (currently the Cadu Barcellos Ecological Park), Inhaúma Hill (the Morro do Timbau favela), the Inhaúma Cove (where today stand the micro-regions of Vila do Pinheiro, Vila do João, and Conjunto Esperança), and Apicú Beach (which used to be a large mangrove area between the Baixa do Sapateiro and Praia de Ramos communities). Maré—tide in Portuguese—was, as its name suggests, an area between tides, located between the Faria River and Guanabara Bay—thus, a naturally flooded and silted area.

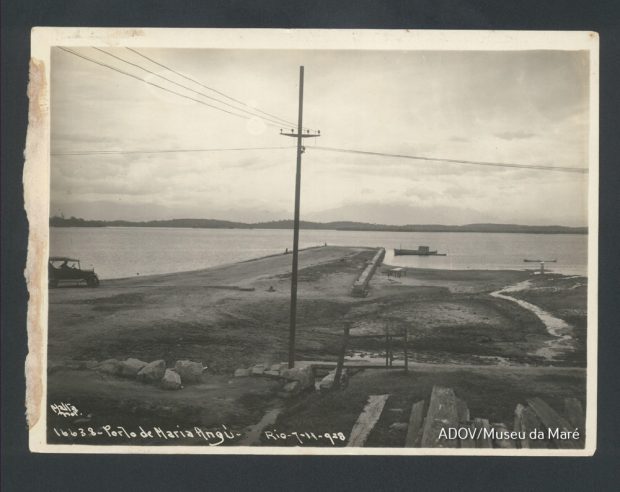

As human transportation occurred, according to the author, predominantly along its waterways, Maré had two ports: Maria Angu, at what is now Praia de Ramos; and one at the foot of Morro do Timbau, along what today is Rua Guilherme Maxwell (better known as Rua da Escola Bahia, near Passarela 7 on Avenida Brasil). This water-based characteristic is so striking in the territory that Timbau and Pinheiro, names of Tupi-Guarani origin, mean, respectively, “between waters” (t´pau) and “spilled” (pi-iêre), according to records from the Maré Museum.

Due to this hydrographic profile, human settlement in Maré has always gone hand in hand with the development of its fishing culture. Making a living from fishing was so common that some Maré communities, such as Praia de Ramos and Conjunto Marcílio Dias, emerged from the settlement of fishing families. Fishing colonies, like those in Ramos (founded in 1923), Pinheiro, and Parque União, resist to this day and stand as living memories of this occupation.

A resident of Parque União, born and raised there, Hélio Ricardo has been a fisherman in Maré for 40 years. He recounts how nature once dominated the region.

“This here [Maré] used to be a small island. The mangrove has always been around. We used to have to come here [to Praia do Coqueirinho, next to the Fundão BRT], wading chest-deep. Sometimes, when the tide went down, we walked with water up to our knees. That was 40, 45 years ago. Back then, we didn’t need much netting to fish—100 meters of net were enough to fill the boat.” — Hélio Ricardo

Carlos Lopes, known as “Cobra,” a resident of Parque União and a fisherman for 50 years, also reminisces about the old days.

“In November, I’d take the groups [of fishermen out fishing]. We’d come back with 250, 300 swordfish. We’d catch the ones we called ‘cachorro,’ the big ones. There were so many of the small ones that we didn’t bother bringing them; we’d just throw them back into the water. I had my shrimp net. Wow! Eight shrimp added up to a kilo! Sometimes we’d catch two boxes of them, real sardines. There was catfish too. There was a time when bluefish came in, and a time when weakfish came along with the croaker. Even snook would end up in the net.” — Carlos Lopes

A centuries-old tradition in the area, fishing gradually changed over the second half of the last century. The availability of fish started to decline due to multiple interventions that harmed the health of Maré’s waterways. These interventions compromised not only the practice of traditional fishing but also the community’s very knowledge of the waters that weave this area together.

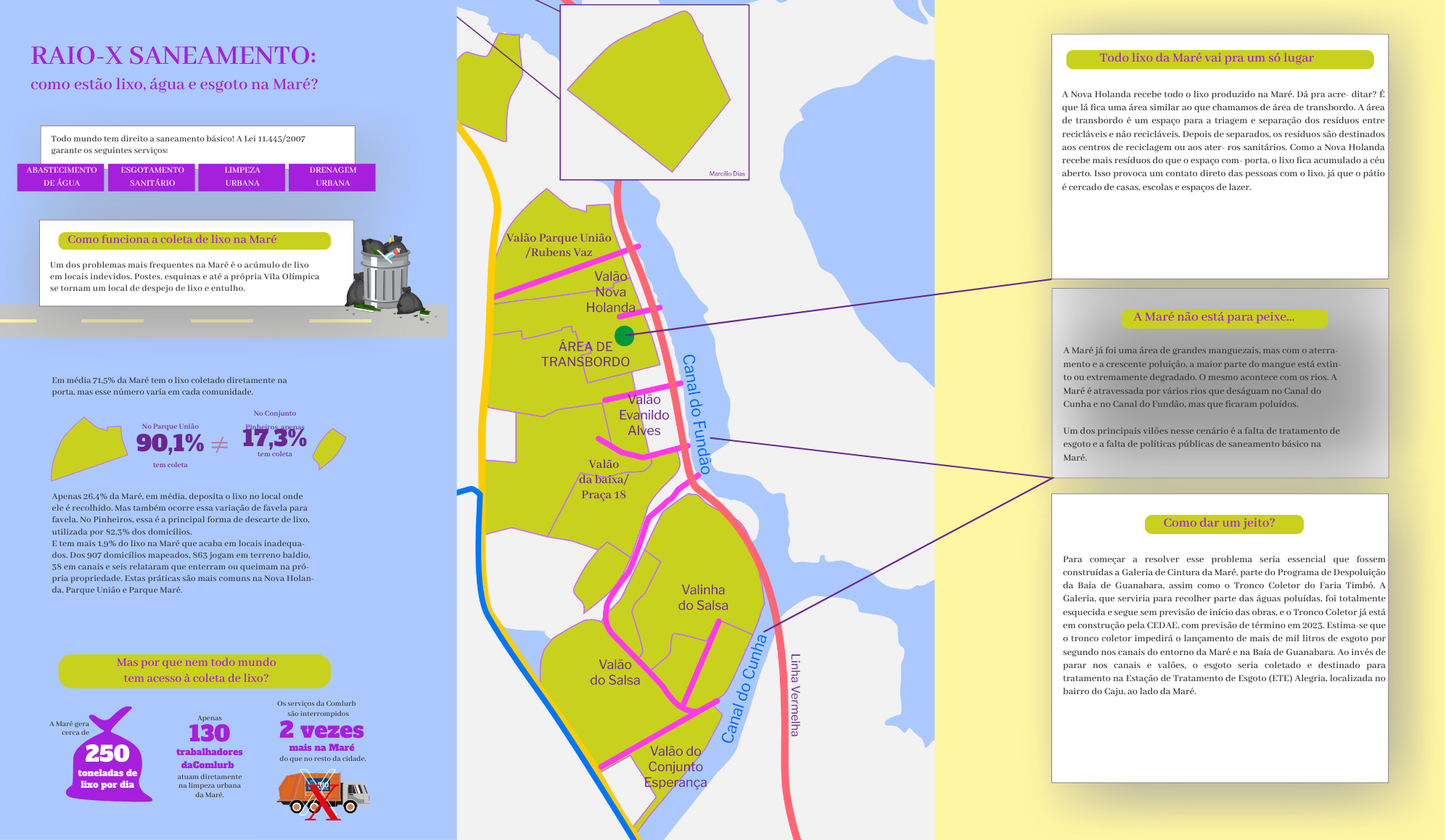

A Portrait of Maré’s Hydrography

Complexo da Maré is located between the sub-basin of Cunha Canal and the sub-basin of Ramos River, with its main waterways being the Fundão Canal—running parallel to the Linha Vermelha expressway—and the Cunha Canal, which crosses Avenida Brasil near the Manguinhos group of favelas. The Fundão Canal, an artificial waterway roughly six kilometers long, was created by the former archipelago’s infilling giving rise to University City, now Fundão Island. It meets the Cunha Canal near Linha Vermelha, at the back of the community, close to Ponte do Saber bridge. Nearly all the sewage outlets from the community and from much of the North Zone of Rio flow into Fundão Canal.

Cunha Canal, on the other hand, which begins near Manguinhos, is about one kilometer long and receives tributaries from other rivers and canals. Some of these are the Jacaré River, which starts in the Serra dos Pretos Forros, a mountain range in the Engenho de Dentro neighborhood, and the Faria-Timbó River, formed by the meeting of the Faria and Timbó rivers near the Inhaúma neighborhood. The Cunha Canal is also fed by tributaries from Manguinhos, Eixo 300, Pinheiro, Conjunto Esperança, and Vila do João canals. All of these cut through the communities of Vila do João, Conjunto Esperança, and part of Vila do Pinheiro, eventually flowing into Guanabara Bay.

In addition to those already mentioned, there are several other waterways that make up Maré’s hydrography. They are, however, less well known—mainly due to inconsistent or insufficient information about them.

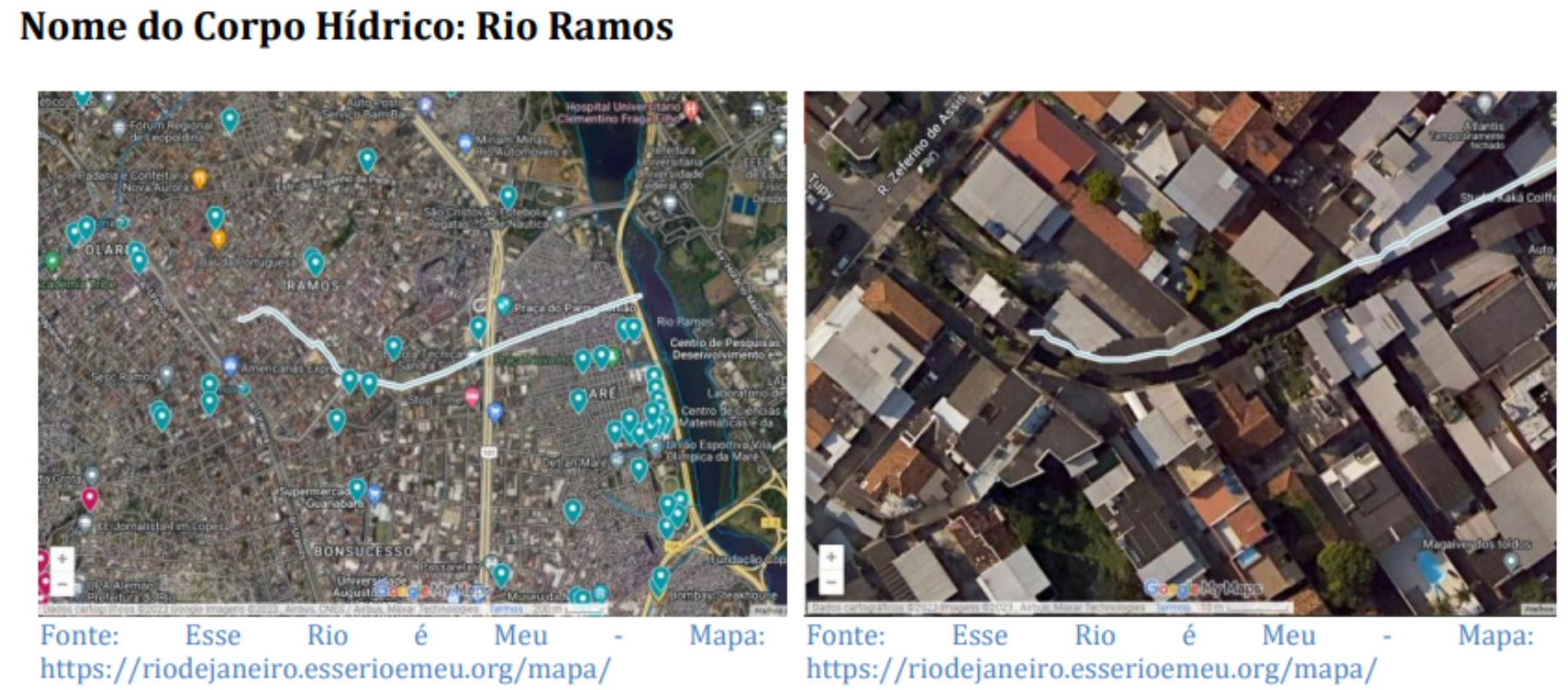

One example is the Ramos River. According to the map from the Esse Rio é Meu (This River in Mine) project, the Ramos River originates in the Ramos neighborhood and, running under Avenida Brasil, enters Complexo da Maré near the Parque União favela before reaching Guanabara Bay. However, while this map presents a straight-line path—from the Ramos River to Guanabara Bay—it references points that differ from the river’s actual course.

One of the reference points mentioned is the Monteiro Lobato Municipal Daycare, located on Rua Tatajuba in Baixa do Sapateiro. The daycare, however, is over 650 meters away from Rua Darci Vargas (commonly known as Rua do Valão), the street through which the Ramos River enters the community. To illustrate the discrepancy: if a resident were to walk from the point where the Ramos River passes Rua Darci Vargas in Parque União to the daycare center in Baixa do Sapateiro, it would take roughly nine minutes along Rua Principal, a street that runs perpendicular to the Ramos River and connects the two favelas.

In addition, all the reference points along this Ramos River route, as described by the mapping, are schools located next to waterways that, within the community, are understood as valões—channels, or potentially canals, where sewage and garbage are routinely dumped. This raises important questions. Why does the map show one route but describe another? Is the waterway on Rua do Valão in Parque União the Ramos River, or just a valão? Are valões merely sewage channels built by residents or the government? The confusion deepens when we look at a study conducted by data_labe, which recorded Maré’s main sewage channels. What the Esse Rio é Meu project identifies as part of the Ramos River, the data_labe study classifies as a valão.

Besides the inconsistencies between the information about the Ramos River presented by the cited maps, residents’ knowledge also points to differing features about Maré’s waterways.

“At Piscinão de Ramos [an artificial saltwater public swimming pool which, despite its name, is located in Maré], we have two [channels]. There’s one at Jet Clube and [another] at the Ramos [Fishing] Colony. In another Maré community, Kelson’s, there are two more: one at [Praia da] Moreninha and another, the largest of them, bordering the Navy area. That one comes from the Brás de Pina and Quitungo areas. The river waters are captured there.” — Carlos Lopes

All these inaccuracies, inconsistencies, or gaps in information about Complexo da Maré’s waterways are linked to a historical process of erasure, neglect, and the mischaracterization of favela rivers caused by urbanization policies. Sérgio Ricardo, director of the Living Bay Movement, explains.

“This is a problem with Brazilian engineering. For over 30 years now, river renaturalization has been underway everywhere else in the world. It’s something that’s been discussed since the 1992 Earth Summit while here we’ve continued to bury and straighten rivers. We have to work with official sources, but through a dialogical process. Some rivers have an official name, but in older communities, fishermen don’t recognize them by that name. They know them by others—usually Indigenous ones. The renaturalization of rivers and their original courses represents a different concept, an environmental one. Here [in Brazil, what’s followed] is engineering without ecology, a hydraulic concept. The same is done with Indigenous issues. How many peoples existed? No one knows. The Fundão Canal, for example, now runs along the Linha Vermelha [expressway]. But did the [original] river really follow that path?” — Sérgio Ricardo

Over the years, housing policies aimed at “progress” did not merely stop at eliminating, filling in, or altering Maré’s waterways. These actions profoundly affected the community’s collective memory and disrupted local ecosystems. Today, many residents experience a sense of disconnection from their natural heritage—a result of interventions that date back to the early 20th century.

The Process of the Degradation of Maré’s Waters

Between 1908 and 2012, the region of the Cunha Canal sub-basin underwent numerous interventions due to its flood-prone nature. Most of these works took place either within or around Complexo da Maré—such as the landfills used to build the former Manguinhos Airport and for the construction of Avenida Brasil (beginning in the 1940s), the infilling of the islands that once existed in Fundão in 1949, and the Project Rio fill carried out from 1979 to 1980, in the area where Maré’s stilt houses once stood.

Aiming to address the issue of housing in favelas, Project Rio carried out a massive land reclamation initiative in the Vila do Pinheiro area. A total of 69 hectares of Guanabara Bay were altered to make way for the construction of 2,300 houses. However, the housing initiative was not accompanied by effective sanitation planning, which led to waste being dumped directly into Maré’s canals and, consequently, into Guanabara Bay.

Seu Hélio laments how Maré’s canals and Guanabara Bay—the main outlet for all these waterways—have become so severely degraded.

“There used to be about 100 fishermen here. We’d head out early in the morning, around six, and by noon we’d be back with four or five [full] trays. That was some 100, 150 kilos of fish. There was anchovy, true sardine [a term for healthy fish], what we call maromba; shrimp, the big kind, the real one; weakfish, snook, stingray… There was such abundance. We once caught over 300 kilos of stingray [in these waters]. [Up until that time, the late 1970s,] you could make a living. I raised my kids on fish, selling fish. But not anymore. Before, there was sand here, but [now everything’s] turned to mud. [These days,] we still catch some [fish], but much less [because of the pollution].” — Hélio Ricardo

All these landfills directly and significantly affected Maré’s canals. To ensure these projects’ feasibility, the works required the construction of artificial drainage channels for the floodable lands—which, in turn, started carrying all the domestic waste from Maré’s communities into Guanabara Bay. In this way, the biodiversity of Maré’s waters gradually gave way to sewage and pollution.

But the neglect resulting from the lack of planning and public investment in Maré’s waterways goes beyond landfilling. In the second half of the last century, the rivers in the Cunha sub-basin underwent aggressive interventions. Once meandering and sinuous, these rivers were straightened, channeled, filled in, or covered by the urban grid in an effort to control flooding.

One of these flood-control interventions was the construction connecting the Faria River to the Timbó River, giving rise to the Faria-Timbó River. This project altered the Cunha Canal—a natural waterway that, in addition to being lined with concrete, was extended due to the merging of the Faria and Timbó Rivers. Today, the Faria-Timbó is a straightened, concreted, and extremely polluted river.

Beyond that, interventions that could potentially improve life in the community still struggle to become reality. In the late 1980s, a project for the construction of the Maré Perimeter Drainage System aimed to treat the sewage running through what is now Rua do Valão. However, as Seu Helio recalls, the project never left the drawing board.

“The sewage that came [and still comes] from Olaria and Penha was supposed to be treated before being released into the Cunha Canal. An old leather-tanning company that’s since closed down, in Penha, polluted a lot because of the chemicals it used. The Parque União street market was supposed to be moved there [to Rua do Valão], but that never happened. The project never left the drawing board. And all that [sewage from the area] ends up here in Guanabara Bay. The tannery is no longer around, but there are still many industries [in Penha] that dump everything into those open drains. And you can see it [when you go by] on Avenida dos Campeões [in Ramos]; it comes down Rua Teixeira de Castro, near Passarela 10, across from Parque União, all the way to the Cunha Canal.” — Hélio Ricardo

Today, the waters that flow through Maré suffer the impacts of all these changes that, over time, have radically transformed the original landscape. Among the consequences are the loss of rivers in the Cunha Canal sub-basin, the near halving of the drainage density of Maré’s canals, flooding, the increased occurrence of heavy rains, and the normalization of river pollution. All this shows that, in addition to compromising residents’ quality of life and the health of Maré’s waters, these interventions failed to achieve their intended goals.

“When Man Wipes Out All the Rivers, He’ll See That You Can’t Eat Money”

Seeking to reverse this scenario, the state government carried out revitalization works on the Fundão and Cunha canals between 2009 and 2011, removing around 3.2 million cubic meters of waste, dredging surrounding rivers, and reurbanizing nearby areas. The dredging allowed mangrove vegetation to naturally reappear in Maré’s landscape. The improvements lasted a mere two years, however, due to a lack of maintenance, showing that the problem cannot be solved in isolation. Lopes vents his frustration over the inefficiency of the effort.

“They only dredged a small stretch, from the Pinheiro bridge to Parque União. That’s it! If you go to Fundão, you’ll see the mountain of mud. The section that needed dredging wasn’t dredged. They should have come dredging all the way here to Ponta do Arassá. They should have started from the canal coming from Manguinhos. The Pinheiro [which receives these tributaries] is unmanageable. [To navigate] There, the fisherman has set times to leave and arrive and has to be in the right spot. It’s a very restricted area for navigating a boat. A large vessel? Forget it. It won’t get through—too shallow, too much mud. And it’s not just mud, it’s filth. Why do they keep dredging the Port of Rio? Because the sea naturally silts up the river, so dredging is always necessary. The same thing would have benefited fishermen here. The water flow to and from these neighborhoods would be much better because we’d have proper outflow here. You can’t pour a bucket of water into a teacup. It will overflow!” — Carlos Lopes

Whether due to failures, the discontinuation of works and projects, or neglect toward favela populations—historical targets of environmental racism—all these interventions have profoundly altered Maré’s natural environment, as well as the relationship between residents, the favela’s ecosystem, and local living conditions.

Branca, as Gileuda Silva is known, has been fishing for nine years with the Prainha Fishermen’s Colony (APAP), located at Praia do Oi in Fundão, and is also saddened by the current state of Maré’s aquatic ecosystem.

“On April 11, 2023, we experienced an incredible die-off of ticonha stingrays. And it wasn’t restricted to Fundão Island. The news went global, and to this day we still haven’t gotten an explanation for why these rays died. Another case was the near-extinction of the swordfish, which disappeared from the Bay for almost three years [between 2022 and 2025]. Most fishermen were worried because, although its commercial value is low, it’s in demand—it’s tasty. Nowadays, catching one is almost like winning a trophy. This happens because of oil spills from ship hold washing, by companies operating in the Bay. They’re the ones that profit the most from nature and that pollute the most. And this is the fishermen’s big concern: which species will be next? Are we heading toward our end? Is there no way to save [our local nature]?” — Branca

This reality affects Maré’s population and their connection to activities such as fishing—a cultural heritage that has always intertwined identity and food security in the community’s life. Thinking about the rivers is, at the same time, thinking about a single Rio (its name evoking both city and river). Environmental policies need to move in tandem with others, such as education, sanitation, and energy policies. The problems facing Maré’s waters, therefore, cannot be addressed in isolation.

“People want to [complain] that there’s no fish, there’s no fish. Of course [there’s no fish]! Everything’s polluted! Fish go where it’s cleaner! Are they going to stay where there’s pollution? Where there’s no oxygen? When man destroys the last tree in the forest, wipes out all the rivers, pollutes, and eliminates all the fish in the sea—that is, our entire ecosystem—he’ll see that you can’t eat money.” — Hélio Ricardo

About the author: Amanda Baroni Lopes has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca and was part of the first Journalism Laboratory organized by Maré’s community newspaper Maré de Notícias. She is the author of the Anti-Harassment Guide on Breaking, a handbook that explains what is and isn’t harassment to the Hip Hop audience and provides guidance on what to do in these situations. Lopes is from Morro do Timbau, a favela within the larger Maré favela complex.